They may not be the varieties that commercial growers concentrate on, but there will always be “new”, old crop species with which to expand your food garden.

They are low input, high output “orphan crops” ~ food plants that were important to people before the simplification of the food supply that accompanied the spread of industrial agriculture, and which can, and should, be important again in an ecologically sensitive, smallholder and homestead focused farming community.

That’s the view of Jason Sampson, curator of the Manie van der Schyff Herbarium at the University of Pretoria, who has made a lifetime study of these ultimate heirloom species.

An unusual, but easily grown “orphan” crop is the “Egyptian” Walking Onion. Of onions generally American cooking teacher, author, and television personality Julia Carolyn Child says “It’s hard to imagine a civilisation without onions. In one form or another their flavour blends into into almost everything in the meal except the dessert.” Sampson adds that onions are an interesting topic in and of themselves.

History of onions

“The genus Allium (which includes leeks and garlic among its ranks) has given the world a number of different species of pungent, edible bulb and leaf crops. These, due to similarities in growth and taste, shelter under the umbrella name of ‘onion’. It can sometimes be very difficult as a botanist to be exactly sure what species, hybrid or other one is working with in a cultivated selection.”

Complicating this is the very long history humanity has with onions. Wild species were harvested by hunter gatherer peoples since time immemorial.

One of the first trade items mentioned between the Khoekhoen peoples and the Dutch settlers at the Cape were indigenous wild onions (Allium synnotii), while Allium cepa (the common biannual bulbing onion and the related perennial shallot and potato onion) has been domesticated in Western Eurasia and the Near East for so long that its original, wild progenitor species is unknown.

The Egyptian walking onion has a fascinating history. Its origins are rooted deep in ancient trade between civilisations and interwoven with the life stories of entire peoples.

Although it bears a name suggesting it has an African source, the story is much more complicated, and has taken genetic research to untangle.

There is however no doubt that this little-known crop should be much more widely grown than it is, and Sampson hopes this article inspires the reader to search out and try this gem of a plant.

Although there are stories that walking onions were farmed in ancient Egypt, science has a different tale to tell, reflected in the Latin name of the plant Allium x proliferum, the “x” in the name indicating a hybrid origin.

Perennial onion

This type of perennial onion (there are different clones, but they are united by similar habits) is a hybrid between two groups of domesticated onions that would never have happened if it hadn’t been for human agency and long distance trade, and further collection and selection for its own, extreme usefulness.

Genetic studies have proven that walking onions are a cross between Allium cepa (the common bulbing onion) and Allium fistulosum (spring or Eastern leaf onion, sometimes known as Welsh onion from the Anglo-Saxon word for foreigner, in this case more specifically meaning ‘Roman’, who likely introduced this species to Europe from the Far East).

Both types have been spread from their origin, eastward for the former, and westward for the latter, along the Silk Road, with naturally occurring hybrids possibly being found, and selected in Northern India/Pakistan in early medieval times. They remain very popular today on the Indian sub-continent and are commonly grown by small farmers.

These selections proved so useful to the nomadic Romani peoples that they spread them through Europe during the Middle Ages, where they became widely grown, and from there they made their way into the Americas in time, becoming an important household crop in homestead and settler communities for generations.

The “Egyptian” name stems from the old-time story that the Romani were “the princes of Egypt”, (which is also the source of the better known, sometimes considered disrespectful, name for these peoples, the Gypsy).

Lazy man’s onions

Walking onions are also known as lazy man’s onions, because they are quite simply so easy to grow. Pest and drought resistant, they tend to persist in areas where they have been planted, and proliferate in two ways. One is clumping at the bulb level, the second is the formation of a cluster of small bulbs, or “topsets” where flowers would normally be in most onions.

It is these topsets that make the plants as useful as they are to homestead farmers, as well as gives them the “walking” label, as these stalks with onions on the end fall over and grow in time, and a clump of onions can “walk” about 1,2m a year if the topsets are not harvested.

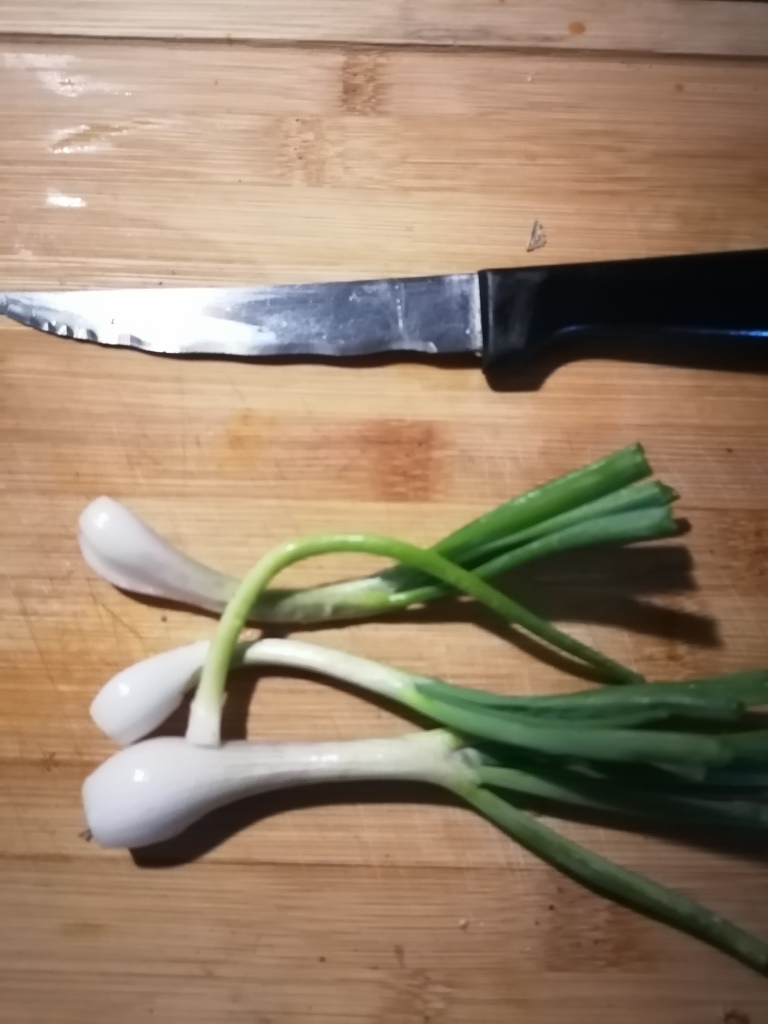

There are two variety types of walking onions in South Africa. The red bulb types are the most common. These produce smaller bottom bulbs that are fairly elongated like a leek, and have a very strong flavour in all parts.

These will often produce topsets on top of topsets, giving them yet another name, “tree onions”.

They are also more or less evergreen if the climate is warm. Most growth is in summer, however.

The second type produces large white to yellow skinned bulbs, and topsets with a pronounced midsummer dormancy and a strong winter growth cycle, although the large bulbs are only developed over early summer after topsetting.

This plant is very shallot or potato-onion like and seems to store relatively well. The flavour is also milder than the red.

Unfortunately, this type is still relatively hard to find, but there are efforts by growers to proliferate the type.

Useful topsets

It is the topsets that make this onion so attractive to nomadic people and homesteaders alike, as producing onion seed, and growing bulb onions from seed, is a tedious and long process.

Topsets can be planted in clumps, and produce decent bulbs for harvest in a single season, producing more topsets during the season, while being harvested for leaf (spring onion) material the whole time.

Topsets can also be used in the kitchen. Some clumps will develop good, pickling onion-sized bulbs in a topset, and good fertilizing will ensure a good harvest of these.

Seed grown bulbing onions can be a bit of a chore as they are very day-length sensitive, meaning you need to choose a variety appropriate for your latitude. But walking onions don’t care, and any one variety can be grown pretty much anywhere with success, helped by the plants being relatively temperature immune as well.

They are grown in areas where the ground freezes in winter with as much success as they give in the Lowveld, although they do tend to be deciduous in the former.

Like all onions they will perform best in full sun with well fertilized soil rich in organic matter.

Producing a constant supply of both bulbs and leaves for the kitchen involves thinking of these plants as a shallot of sorts. One should maintain a mother plant bed of mature bulbs and clumps which is only split when they get too dense.

Topsets should be planted out without splitting as soon as they are fully developed and the stalk holding them aloft starts to bend to the ground. Then allow a season to develop for the kitchen, after which they can be harvested bulb and all.

Bottom bulbs can also be used to start new clumps of onions, and the mother bed can be used as a source for these in early autumn for the white variety, and most of the growing season for the red.

Clumps and single bulbs that develop from these will also be ready for harvest in January through to March.

You can harvest new foliage for spring onions at any time, and one can also produce blanched necked ‘negi’ onions with particularly the red walking onion types common in South Africa by hilling the soil around them.

The plants are also remarkably tolerant of weed competition, which most onions have problems with, and are pest and drought hardy.

Topsets and the bottom bulbs of walking onions can potentially last for months if fully developed and kept somewhere cool, dark and dry, but it is best to keep your plants growing actively as long as you can.

Propagation material is available from certain seed savers and seed merchants during the growing season, and certain speciality nurseries are beginning to offer established plants in bags.

“Perennial onions are a particular favourite of mine,” says Sampson, “and I hope that this article will inspire you to grow your own walking onions, and maybe some growers to experiment with other types of long lived, clonal onions, such as potato-onions, which are virtually unknown in South Africa.”

For more information on this, or other orphan crops, please contact Jason Sampson at jason.sampson@up.ac.za. All pictures courtesy of Jason Sampson.

I had some shat you call potato or multipier onions I found in Riviersonderend and grew them very successfully in Greyton (WC). They do not grow w nil a on the stems. You simply plant plant a small onion and it will they grow a whole bunch on top of the ground. I no longer have that land and am searching everywhere for some of these. Please let me know if you might have some for sale