This is the second in a five-part series called Fluid Waste Management & Septic Tanks. To read part one, click here.

A fluid waste management system ~ any system at all, including municipal systems ~ should ideally operate on the principle of “out of sight and out of mind”.

However, for it to do so requires its users to be responsible in what they put down the system. If you put inappropriate stuff down the drain, the system will soon rebel and come back to “bite you on the bum”. Sometimes almost literally.

In short, the only things that should go down the drain, whether a kitchen sink, a bath or a toilet, should be organic. In a septic tank set-up the exception is toilet paper, with the proviso that it should be single-ply (twin-ply or triple ply takes too long to digest).

Thus, cotton wool, female sanitary items, earbuds, disposable nappies, wet wipes, cigarette butts and, nowadays, disposable face masks, should be discarded into a waste bin, not the loo.

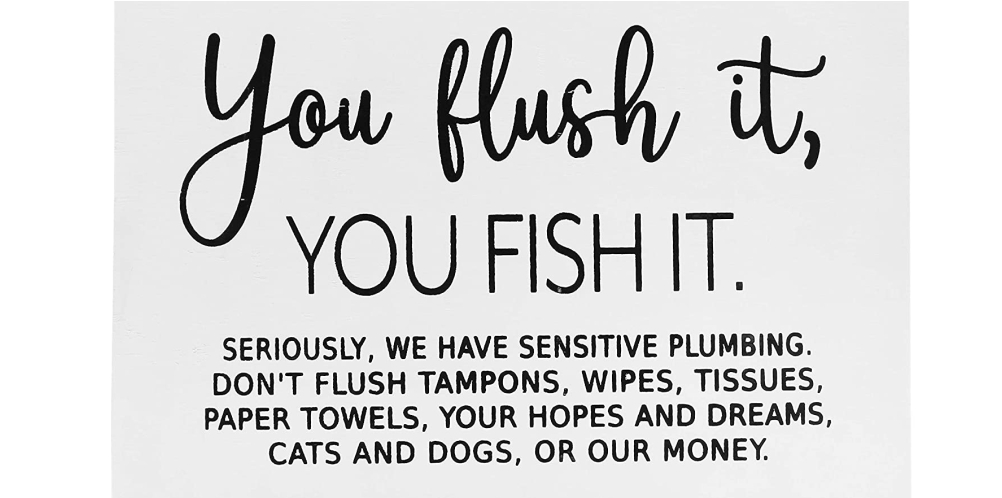

Household members and guests should be encouraged to dispose of such items into a small bin placed next to the toilet pan, the process being greatly encouraged by the addition of small paper bags left conspicuously on top of the cistern cover. A sign on the wall above the loo, with suitably humorous wording, will also draw users’ attention to the necessary procedure.

Toilet cleaners, especially those that advertise that they “kill 99,9% of all household germs”, should be checked for suitability with a septic system, and should be used sparingly. The aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in your septic tank, on which you rely for the digestion of waste, are, after all, germs.

There are also two “organic” items that should be disposed of separately, namely human hair and “fogs”, which stands for fats, oils and greases. Human hair, from whatever part of one’s anatomy is the one human substance that the microbes of a septic system won’t digest. And, over time, human hair will foul the impeller of any dewatering pump you might have in the system.

Likewise, fogs will settle in pipework and together with soap suds form a hard, white lining that will eventually clog the pipe, much like the build-up of fat that will clog your arteries and can kill you.

And, such oils and fats that make it into the system will, eventually, line the surface of the soil of your soakaway, closing off the soil’s ability to absorb fluid.

Also to be avoided are chemicals, particularly caustic soda, which is commonly used to unblock fat blockages, carbolic acid products (Jeyes’ Fluid), and also any hydrocarbon (petrol, motor oil, paraffin etc), and medicines.

There are formulations one can (and should) put down one’s septic tank. We will cover those in tomorrow’s story.

These points apply equally to all fluid waste disposal, including municipal systems. A relatively recent development in many cities has been the emergence of “fatbergs” in sewer tunnels. These are large (up to 500m long) solid blockages of the tunnel, comprising a mixture of wet-wipes, disposable nappies and other inorganic items, cemented together by congealed fogs and soap components. Not only are these fatbergs difficult and hazardous to remove, but blockages of large city sewers in such a manner can result in pressures building up in the system which see explosions of raw sewage into residents’ homes, up drain lines and toilet pipes. Hardly a pleasant prospect should one be performing one’s daily ablutions on the loo at the time.

And, chemical analysis of waste water is starting to reveal alarming levels of residual drugs, many of which are hormonal in nature, and which are starting to affect the breeding patterns of species that rely on, or live in, the treated effluent, for example fish in the rivers into which treated sewage is discharged.

For Part Three, click here.